On the outside: A 366-foot-high orb dotted with thousands of puck-sized lights that when combined are capable of displaying massive eyeballs, bouncing basketballs, winking happy faces, and other animations across a 580,000-square-foot expanse of screens to planes and mesmerized passersby. Inside: 160,000 speakers booming out music to audience members watching videos swirl overhead on an LED screen larger than three football fields. Plus, a museum. And retail space. And restaurants. And gaming.

The Sphere at the Venetian — lauded as the world’s largest spherical structure — is the most iconic architectural addition to the Las Vegas Strip in decades, and has become the envy of city planners around the globe.

But how does such a behemoth beacon of technology come to be designed or built — or even imagined? And how does it fit in with other longtime, recent, or upcoming examples of architectural artistry that are part of the ever-evolving Las Vegas skyline?

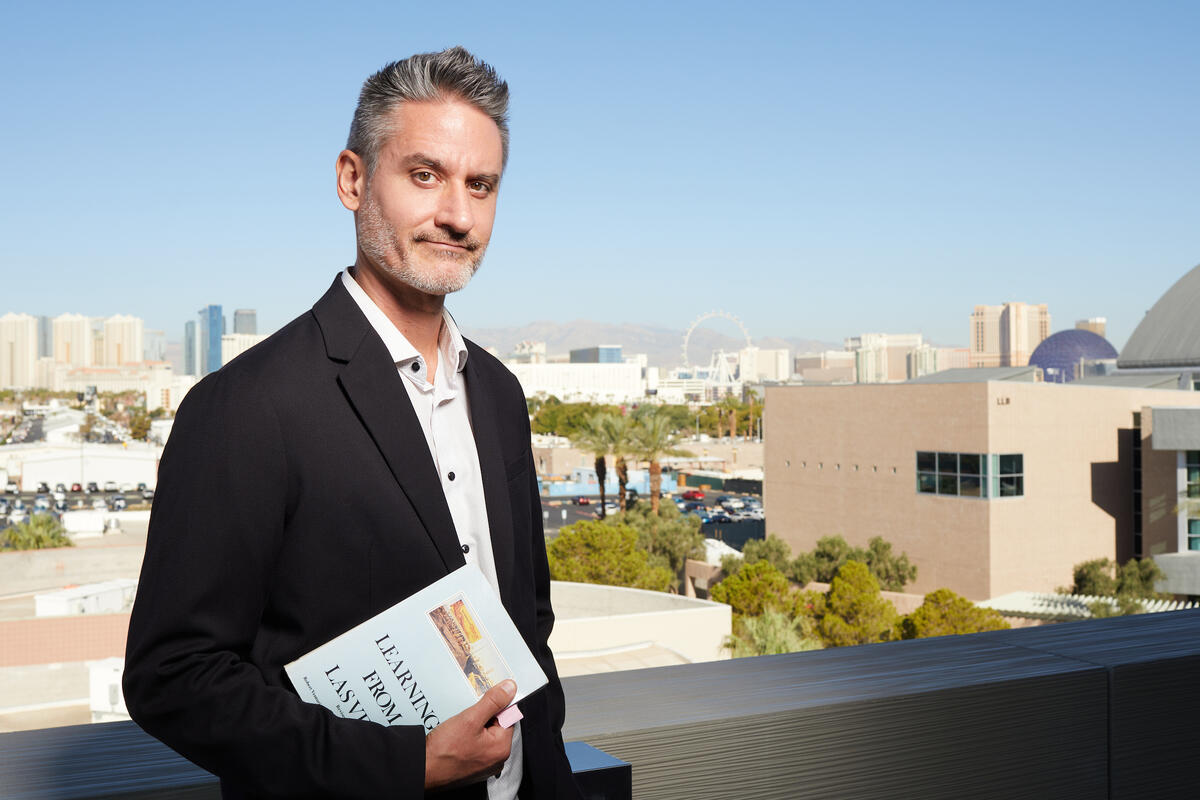

For an inside look at the nuances of designing the Strip – and how the Sphere is boosting Las Vegas’s reputation within the global hospitality architecture industry – we turned to School of Architecture professor Glenn NP Nowak. As the founder of UNLV’s hospitality design program, Nowak leads courses that connect students in real time with architecture education, design professionals, and experiential opportunities.

This winter, his students were among the first to get a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the Sphere’s construction during a class site visit. The $2.3 billion, 17,500-seat entertainment venue debuts with a U2 performance on Sept. 29.

“The projects in Las Vegas and the projects that Las Vegas firms export to other locations around the world are unlike any other buildings you see anywhere,” said Nowak, who himself worked on various Strip projects for local design-build firm Marnell Architecture before academia.

“I realized that many architecture schools, including the one I went to, don’t prepare students to work at that scale: millions of square feet, thousands of hotel rooms, all these different building occupancy types — like convention, retail, restaurant, casino, the list goes on and on — under one roof,” he said. “Each one of those could bring in a unique set of specializations and they come together to create an archetype that you only see in a few places around the world.”

Read on for Nowak’s insights on designing buildings and attractions for the Las Vegas Strip versus residential areas of Southern Nevada; the role of new technologies, accessibility, and urban issues in hospitality design; and the ways course, research, and internship opportunities here at UNLV fit into the changing architectural landscape.

How has the Las Vegas skyline changed over the decades?

The changing skyline makes me think of the Dreaming the Skyline project — which I collaborated with UNLV Lied Library’s Special Collections on — that digitized construction documents of resorts on the Strip from the 1950s, 60s and 70s. This digital archive allows you to see how rooms in the 50s and 60s were half the size of what they are now — kind of like our homes are three to four times the size of what they used to be. You can see how the buildings have gotten more sophisticated. They’re not just bigger, they’re in many ways smarter. We’re looking to add images from the 80s, 90s, and 2000s to the collection to really show that measurable change over time.

Speaking of design changes over time, what in your opinion are examples of architectural excellence on the Strip?

Every new and improved property comes with a caveat — they’re excellent in a given place and time. What might be a tired structure, or an example of what not to do, might’ve been great 30 years ago. And the Strip evolves at such a fast pace – so many of our buildings have been completely remodeled, torn down, and rebuilt.

One of the more recent examples of greatness is the Cosmopolitan, which is built with a unique vertical design. It’s unusual to see restaurants on top of a casino, and meeting space on top of that, and a pool on top of that, and not to mention the parking down below all that. They did a great job of fitting all of these different programs into a really compact site. Most integrated resorts would take up three or four times the amount of land, but they’re able to deliver a great — and maybe even a better — experience because things are so close. You don’t have to walk a quarter mile from your car to the front desk, and you can get around pretty easily with vertically-connected escalators and elevators.

On the flip side, theming has waned in popularity. And that’s what some people would term “bad architecture.” It’s just a great example of embracing a modern aesthetic, which some people might consider a theme in itself. There’s a choice to design with minimalist curtain wall systems, steel, and glass. Some of the themed properties really did an amazing job of sending their design teams overseas to study historical architecture and bring back a pretty deep understanding of what made those earlier structures so engaging. But the Strip is always evolving and responding to new challenges.

What kinds of innovation do global tourists of today expect in casinos and other entertainment/hospitality venues, and how does the new Sphere fit into that?

The uniqueness of the experiences here are a big draw, and many of the newer venues are being designed to really curate only-in-Vegas kind of experiences — most of which happen indoors — that can be replicated time and time again.

I think architects play a huge role in shaping that human experience. Using the Sphere as an example, I took about 40 of my undergrad and graduate students there this past winter because the construction of that venue is unlike anything we’ve seen.

There’s a really complex method to the madness of designing something like this. The structure is massive enough to fit the Statue of Liberty inside. Builders brought in the biggest crane ever to touch ground in Las Vegas. And the sequencing of the construction process is unique: As the dome was built, the center remained open so they could drop more equipment and rigging inside. And it’s truly an only-in-Vegas project with a scale that’s as much as 10 times bigger than the largest Imax theater, which is probably the most technologically-advanced comparison I can think of. This needed to be a really hefty structure in order to hold the kind of performance equipment – lighting, LED screens, massive sound systems, all hanging from this concrete and steel structure — that the Sphere is being built to offer.

It’s just a different beast from everything.

Tell us more about your students’ visit to the Sphere construction site.

The Sphere tour was part of our clinical internship class, which allows students to visit a construction site to compare architectural drawings to the work in progress and also accrue experience credit toward their architecture licensing exam.

For background: Architects are the ones dreaming up the idea of putting up LED screens around an acre of space on a dome, understanding very generally what is needed to make that happen, and allocating rough dimensions for the structural depth of all of the building systems. But that technical expertise is coming from several other disciplines outside of architecture.

The Sphere visit gave UNLV students a first-hand look at the blueprints. And we had someone from the construction team’s audiovisual department, a contractor, and a project architect all answering questions so that the students could understand how the vision of the design team – which was based in Kansas City – would translate from paper to pillar. But then another level of detail is not just building it, but making sure that the end goal – these performances – create a world-class audiovisual experience and actually go off without a hitch.

How should architects think about designing for residential areas throughout Southern Nevada versus the Strip?

There are lessons to be learned from hospitality design — and specifically the architecture of the Strip — and applying that to not only our homes but our residential communities in a way that makes them more hospitable. Part of what makes some of those resorts so great is that they're compact: you can wake up and find a great place to eat or shop nearby. Imagine if you could do that in your neighborhood. Most of us have to get in the car, drive several miles to go get a coffee, then hop in the car again to drive several more miles to shop or work. But creating an integrated neighborhood that plays off the idea of integrated resorts that pull all these different programs together would eliminate our region’s very segmented urban design that leaves large swaths of barren land and disconnects residents from their housing or place of work.

I recently spoke with an HR professional from a big firm in San Francisco who said the lack of available housing is increasingly a barrier to recruiting talent. The Las Vegas housing market might be a little friendlier, but it’s still a challenge, especially for young people. Let’s take, for example, Fontainebleau on the Strip, and Durango, a new resort opening up on the southwest side of town — they’re looking to hire a ton of people. These are just two of many instances where we can glimpse how the discussions on hospitality, economics, and residential housing are intertwined.

We’re close to Boulder City, one of the first company towns that was created to house workers who built the Hoover Dam. Similarly, when opening major worldwide attractions, how are we simultaneously rethinking the neighborhoods that are going to support that?

How does UNLV’s School of Architecture help prepare students to design high-caliber venues that offer these kinds of unique experiences?

It’s a really unique program. Many schools of architecture would never touch the history of Las Vegas architecture — which is a shame because so much of the design that occurs here is replicated all over the world. And often, it’s local architecture firms that get called upon when Singapore, Macau, South Africa, or Dubai are thinking about building the next great integrated resort.

When we started this hospitality design concentration back in 2010, I think those leading architects, many of whom are UNLV alumni, really saw an opportunity to cultivate the next generation of design professionals. By leaning on those local professionals — bringing them into the classroom as guest speakers or critics — our students are exposed to the unique intricacies of designing world-class structures. And it’s an opportunity not just to say “this is how you do it,” but to look at buildings on the Strip and really think of ways to do this even better.

Additionally, the School of Architecture requires students to do internships and the vast majority of firms that participate either specialize or dabble in hospitality. That’s great because you could apply hospitality design to virtually any building type. With our students receiving this important training early on in their careers, more and more architecture firms are looking to hire our emerging talent.

And our current students keep the pipeline going. For the last decade, we’ve required each graduate to develop a design thesis project that tackles a critical issue related to the hospitality industry. The projects, along with industry feedback and notes on lessons learned, are recorded in a digital archive for future students to review and build upon.

Have UNLV students come up with cool concepts in their theses that could revolutionize the industry?

Tons of cool ones! I teach two graduate-level courses focused on independent design investigation.

We’ve had students look at on-site food production built into resorts. Some have looked at the urban navigability of the Strip sidewalks, such as aerial tramway systems to benefit wheelchair users. Other students have examined ways to use driverless vehicles to free up almost half of the valuable land on the Strip that’s currently dedicated to parking garages. And yet others have delved into healthcare design — think of anything from medical tourism to designing hospital rooms in a way that recognizes patient well-being and satisfaction is often tied to how patients feel they've been treated. That integration of psychology applies as well to designing schools and retail spaces that move them away from being historically cold, clinical spaces to more welcoming spaces.

In recent years, we’ve had a number of students look at the emergence of sports facilities and envision ways to make those perform more often and in ways that are more connected to the community. For example, rather than use an arena just a handful of times each year, how can you rethink the design so that perhaps many smaller pieces of it could be activated year-round or even during a season activate them midweek instead of just seeing them come to life on weekends or game day? Could they somehow be an even greater catalyst for economic prosperity of the area around it?