"Baroque” is a word that music historians typically apply to the period between 1600 and 1750. As an art-historical term, this word comes from that period itself: in 1734, a reviewer for the Mercure de France wrote the following about Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera, Hippolyte et Aricie:

"[The opera] had no tune...[and] the music had no relationship to the dance except for its more or less lively movement. There was consequently no thought, no expression at all. It ran through every trick with speed, unsparing of dissonances without end. ... Continually it was sadness instead of tenderness. The uncommon had the character of the baroque, the fury of din."

The ideas expressed by this cantankerous critic might surprise people who love the music of Bach, Vivaldi, and Handel (surely the most popular “baroque” composers). But for the 18th-century reader, “baroque” was most definitely a dirty word, meaning distorted, grotesque, unnatural. Its origins outside of music lay in jeweling, from the Portuguese barroco, applied to pearls that were misshapen. “Baroque” captured a sense of deep disappointment: The idea that one hoped to encounter something beautiful, something pristine, and instead encountered something affronting, bizarre, even ugly.

I would love to disabuse this grumpy French critic of the idea that “baroque” music is ugly, since I consider this period’s music to be the most aesthetically satisfying of all time. Yet, even I must admit that harshness and imperfection is, indeed, at the heart of what makes this music work — and has been since the very moment we say baroque music was born.

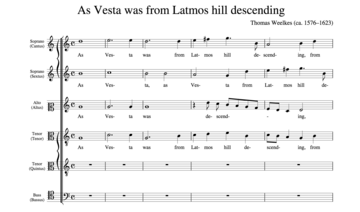

That moment took place around the turn of the 17th century, in Italy, where Claudio Monteverdi was writing madrigals in the venerable tradition of the previous century. Madrigals were a rich site for compositional experimentation. These were pieces for multiple singers that utilized single stanzas of text, without refrain or other formal crutches for composers to structure their music. Musicians were thus required to link their sounds to words at a detailed level, if the music was to bear any relationship to the text. In the Renaissance, solutions were sometimes exquisite and sometimes banal, but almost always delightful to listeners. Below is an example of one of the most famous madrigals of early 17th-century England, in which the composer cleverly depicts various characters meeting as they go up and down a hill by having the music first “go” up the hill and then tumble down it (soprano and alto, measure four).

Monteverdi, one of the most lauded producers of madrigals, was working in this tradition of close word-music relationships when he inadvertently ushered in the baroque period. The problem with being lauded, of course, is that there is always someone who doesn’t think that the reputation is deserved—and Monteverdi certainly had his detractors. The most infamous was Giovanni Maria Artusi, a music theorist. In a publication dated 1600, Artusi reported that he had been to a dinner party with a group of musical cognoscenti, and was appalled at the popularity of Monteverdi’s madrigals, which most certainly did not follow the proper rules of music theory. He therefore set out to dismantle Monteverdi’s reputation.

Artusi’s argument was logical enough, and had roots back to Pythagoras and Plato. The old Greeks had established a harmonic theory that has more or less never left us. It posited that certain sounds are consonant and harmonious, while others are dissonant and inharmonious. Less than a century later, Plato used this information to build a whole mythology of music, said to be, at its best, representative of the harmony of nature, of society, of the cosmos; at its worst, sound was a disharmonious, dangerous, and destructive force. Armed with this information, Artusi and his school argued that, if dissonances were to be used, they needed to be treated very carefully to ensure that the music produced was beautiful. The rule was simple: “prepare” the dissonance with a consonance, sound the dissonance, and then “resolve” it into another consonance. The example below allows you to hear an example of the full procedure.

Artusi encountered in Monteverdi’s music flagrant violations of these principles. One madrigal in particular, “Cruda Amarilli,” contained blatant, unresolved dissonances from its very opening measures. The full vocal ensemble opens on a G-major triad. The bass then moves to an E, creating a harsh dissonance with the D in the top voice. Although this is a pretty strident and shocking sound to open with in16th-century terms, Monteverdi hasn’t yet violated a rule. But when the next note change happens, Monteverdi committed his cardinal sin: as the soprano’s D moves to a C, the bass moves to a B, creating yet another dissonance without resolving the previous dissonance. To make matters worse, an A in the second voice from the top created another dissonant interval with the bass. There was only one explanation for this use of dissonances upon dissonances, said Artusi; Monteverdi was just a bad composer, and people who enjoyed his music had depraved tastes.

Monteverdi did not take such abuse lying down, and responded in a printed document of 1607. Artusi, Monteverdi said, was no musician, but a mere theorist; he had no experience actually creating music that people liked to hear. Moreover, Artusi claimed to have read ancient sources, but he simply didn’t understand them, Monteverdi said. Plato himself had not only been talking about tones when he talked about the potential of music as a moral force; his writings referred to the union between words and tones, poetry and music. Therein lay the power of music — to give emotional expression to the semantic meaning of words.

And what were the words here? “Cruel Amaryllis, who with your very name / teach bitterly of love, alas!” This text evoked the ancient Greek story of Amaryllis, a pitiful nymph who stood on the doorstep of a shepherd who would not return her love, and stabbed herself for 30 days with a golden arrow, until she died in a pool of blood. The gods, taking pity on her, transformed her blood into a beautiful red flower. This madrigal then expresses the familiar combination of beauty and suffering that love inspires. These are ugly — or at least painful — concepts. And such concepts call for dissonant music, Monteverdi claimed.

Of course, Monteverdi’s music here isn’t “ugly” at all. These dissonances are spine-chillingly, mouth-wateringly beautiful. Their violations of the old rules of counterpoint, their insistent sounding and resounding of dissonances, is ugly on paper, ugly in theory, but profoundly moving in practice. It is hardly “natural”; this concatenation of dissonances is carefully contrived to correspond with the meanings of the words. It is hardly “simple”; an appreciation of Monteverdi’s art requires close, blow-by-blow analysis. It is complex, tortured, an expression of pain and loss. This work stands as a fine early example of the aesthetics and approaches that would come to dominate the musical world for the next century.

It is, in a word, “baroque.”