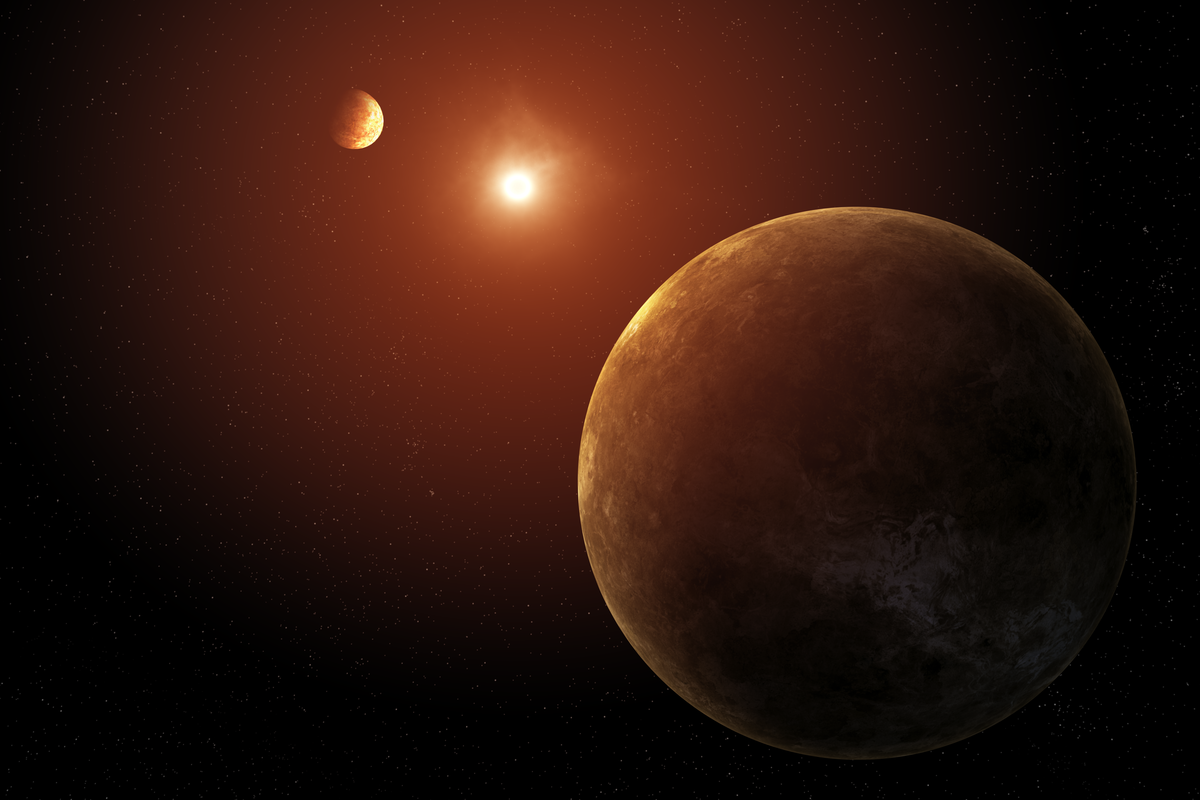

A system of seven sweltering planets has been revealed by continued study of data from NASA’s retired Kepler space telescope: each one is bathed in more radiant heat from their host star per area than any planet in our solar system. Also unlike any of our immediate neighbors, all seven planets in this system, named Kepler-385, are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

The ability to describe the properties of the Kepler-385 system in such detail is testament to the quality of this latest catalog of exoplanets, or planets orbiting distant stars.

"Now that we've had some time to mull over the data, we've been able to improve our estimates for some of the properties of the planets in these different systems, like their orbital periods and sizes,” said Jason Steffen, a professor of astrophysics at UNLV and an author on the paper. "It's the ultimate catalog of the planets from the Kepler mission."

Kepler-385 is one of only a few planetary systems known to contain more than six verified planets or planet candidates. The system is among the highlights of a new Kepler catalog that contains almost 4,400 planet candidates, including more than 700 multi-planet systems.

“We’ve assembled the most accurate list of Kepler planet candidates and their properties to date,” said Jack Lissauer, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley and lead author on the paper presenting the new catalog. “NASA’s Kepler mission has discovered the majority of known exoplanets, and this new catalog will enable astronomers to learn more about their characteristics.”

At the center of the Kepler-385 system is a Sun-like star about 10% larger and 5% hotter than the Sun. The two inner planets, both slightly larger than Earth, are probably rocky and may have thin atmospheres. The other five planets are larger – each with a radius about twice the size of Earth’s – and expected to be enshrouded in thick atmospheres.

“Somehow, someway, our solar system avoided forming a planetary system like these Kepler systems,” said Steffen, who studies exoplanets. “And if it had, we wouldn’t be here.”

While the Kepler mission's final catalogs focused on producing lists optimized to measure how common planets are around other stars, this study focuses on producing a comprehensive list that provides accurate information about each of the systems, making discoveries like Kepler-385 possible.

“This new research shows that even though the Kepler mission is over, there’s still a lot of information to be pulled from it,” he said. “By studying these distant planetary systems, we get a better sense of our own history and how it diverges from the histories of these other systems.”

The new catalog uses improved measurements of stellar properties and calculates more accurately the path of each transiting planet across its host star. This combination illustrates that when a star hosts several transiting planets, they typically have more circular orbits than when a star hosts only one or two.

“The fact that NASA keeps a repository of all its historical data actually is a really useful tool for future astronomers because the data are still good,” said Steffen. “And in this case, these are still the best data and probably the best data we will get on these types of planetary systems for decades into the future.”

Kepler’s primary observations ceased in 2013 and were followed by the telescope’s extended mission, called K2, which continued until 2018.