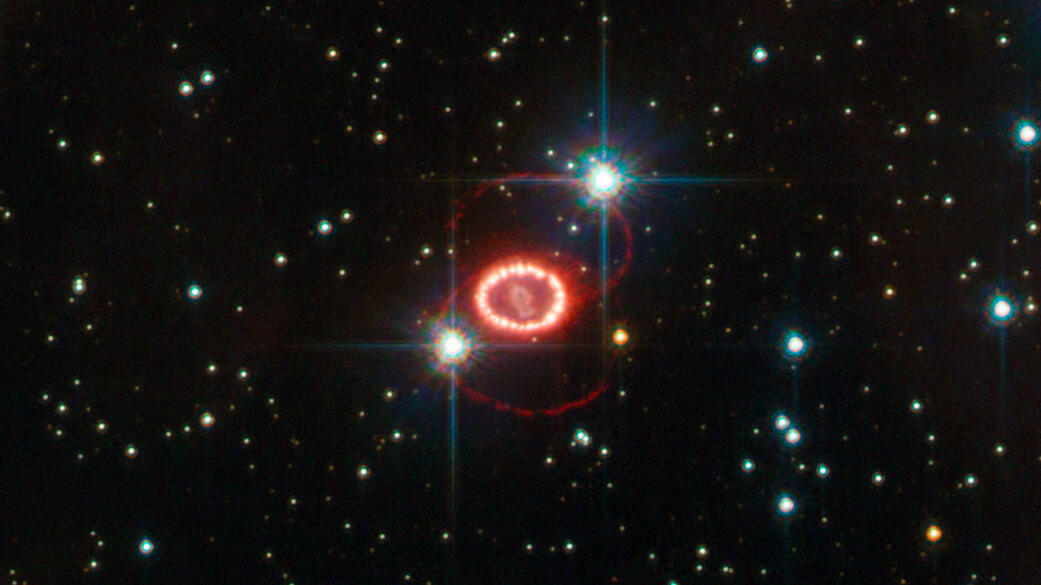

Stephen H. Lepp is the chairman of UNLV's department of physics and astronomy. At 7:30 p.m. March 23, he will present "Supernova 1987A: Thirty Years Later" at the Marjorie Barrick Museum as part of the University Forum lecture series. Here, Lepp discusses what we learned from the first supernova visible to the naked eye in 400 years.

On Feb. 24, 1987, a supernova was discovered in the Large Magellanic Cloud. A supernova is an explosive end to a massive star. This supernova was bright enough to see with the naked eye, the first such in nearly 400 years and the first since the invention of the telescope. As such, this was the first bright supernova to be observed with modern scientific instruments. It was the first from which neutrinos were detected, the first in which molecules have been detected and the first where we have observations of the star before it blew up.

Stars begin their life in dense molecular clouds. These clouds, which exist between stars in our galaxy are basically star forming factories. Parts of the cloud can collapse to form dense objects which eventually burn hydrogen up to helium in the process of nuclear fusion. This is the most common configuration for stars, and almost all the stars you see in the night sky are undergoing this burning of hydrogen to helium.

Most of these stars are not massive enough to get temperatures high enough to burn anything beyond hydrogen, but the most massive stars will undergo a series of nuclear reactions burning elements all they way up to iron. Iron is the most tightly bound nuclei and so you cannot produce energy by converting iron to higher mass elements. The massive stars can undergo a processes called core collapse and the energy released out shines for a short time the entire galaxy. These explosions look like new stars and so were called nova or supernova.

In this talk we will cover the history of supernova observations and some interesting results from Supernova 1987A, along with some modern supernova research.