Just when it seemed like we could sit back and breathe a sigh of relief from declining COVID-19 rates in Nevada, another virus started making headlines: Monkeypox.

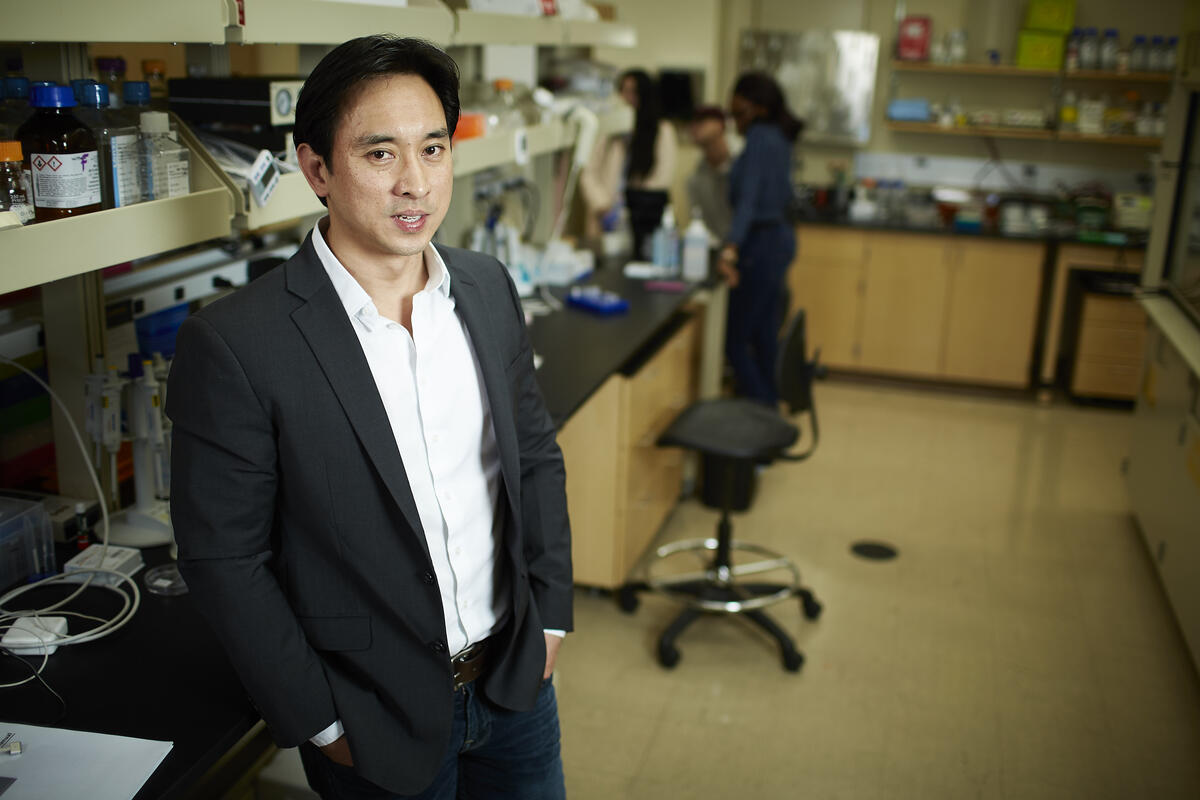

Local COVID cases have been on a downward trajectory for more than a month. But a wastewater surveillance program led by UNLV Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine professor and infectious disease expert Edwin Oh has started tracking monkeypox, making Southern Nevada among the first few metropolitan areas nationwide to begin searching the sewers for the emerging virus.

Oh and colleagues from the Southern Nevada Health District have been watching our wastewater throughout the pandemic, work that’s helped identify new COVID variants in our community weeks ahead of more traditional testing data. The team’s wastewater surveillance program has been vital in helping us navigate the oftentimes murky waters right in front of us – giving advance notice of vital health information to our families, businesses, and state agencies.

“Las Vegas is the international capital of tourism and a major metropolitan city, so we predicted that we would be able to use wastewater to track the spread of monkeypox,” said Oh. “The intent of obtaining this information is to stay one step ahead of potential community transmission.”

The team has used its growing wastewater surveillance program to track COVID variants, flu, and – now – monkeypox, by routinely analyzing samples from water treatment plants and strategic sewer locations spread throughout the region. The goal now is to define whether the amount of monkeypox virus in our communities is increasing, or decreasing, over time, and to understand if unique variants emerge.

According to Oh, the monkeypox signal is relatively low right now locally, but he hopes the work happening here can be used by other cities to monitor the ongoing public health emergency. We caught up with Oh to learn more about the new phase of the wastewater surveillance program, and to get his thoughts on what the future holds for monkeypox monitoring in Southern Nevada.

When did your surveillance program first detect monkeypox in Southern Nevada wastewater? How is your team able to identify these viruses before anyone else?

When the first case of monkeypox was reported in May 2022, my colleague Dan Gerrity with the Southern Nevada Health District and I leveraged the infrastructure in place and started developing the tools and protocols to detect monkeypox viral DNA. Our first positive result was in mid-to-late July 2022.

A major reason why we are able to find pathogens faster than many labs in the world is that we have a highly motivated group of UNLV undergraduate students who lead the collection, processing, and analytical components of the program.

I have been fortunate to be affiliated with world-class institutions during my career, but this is the first time that I have observed young students leading the charge to obtain data seven days a week.

How much should tourists and locals truly be worried about monkeypox?

I don’t think that our community of locals and tourists should fear the results. They should, rather, be empowered to learn more about an infectious disease that has spread to many countries in the world.

When COVID-19 started circulating in early 2020, many people in our country did not think that they would be affected. Our monkeypox data reminds the community that we should stay vigilant and our data will also let us know when monkeypox viral levels start to dissipate. Fear leads to paralysis. However, data leads to better-informed decisions.

How widespread is monkeypox in the U.S. and the rest of the world?

Monkeypox was recently declared as a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization. This designation is reserved typically for the most serious outbreaks and has only been declared a few times in the last 20 years.

The U.S. also declared monkeypox as a public health emergency. Case numbers are relatively low in Nevada currently. But data from our wastewater surveillance suggests that case infections may climb at a very fast pace in the next 30 days.

How many strains are there, and do you expect the virus to mutate — similar to coronavirus?

Monkeypox is caused by a virus that was first discovered in colonies of monkeys in the 1950s and the virus has remained endemic to west and central Africa.

The outbreak in 2022 has puzzled many because of the sudden growth of infections in countries that do not commonly experience monkeypox infections. We think a reason for this explosion in cases is because of mutations, which have resulted in at least two different monkeypox strains.

Genomic surveillance (understanding how variants impact public health) for pathogens has typically been reactive and we are now sequencing additional genomes to answer this question with more precision.

We do not expect the monkeypox DNA virus to evolve as fast as what we have seen with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. However, genomic surveillance of monkeypox has not been a priority previously, and I believe we are going to learn a lot more over the next 60 days.

How accurately does wastewater reflect the virus’ presence in our community? And why is tracking the virus important?

A major advantage of wastewater surveillance is that any pathogen that is shed (through urine, feces, skin lesions, and saliva) and enters the sewage system through toilets, drains, and sinks can be collected and examined in the lab.

The data obtained leads to a population-level summary of anonymized results. Such information can then be shared with public health officials, and both testing and vaccination teams can be prioritized for zones with higher infection levels.

We think that operationalizing wastewater data can lead to the more efficient deployment of resources. For example, if there was a new variant that was circulating, deploying a wastewater surveillance program will likely lead to the identification of the variant.

If we know that antiviral medications or vaccines only work for some variants and not others, we will have new clues on how to deal with an outbreak without testing a single human.

Why is it important to work with other public health agencies and jurisdictions to address these viruses?

When a wastewater program is coupled together with actions from public health agencies, state officials, environmental engineers, wastewater plant operators, and businesses, we can truly see how interdisciplinary science and public policy make a difference in a community.

Let me give you an example: I am concerned about the impact of monkeypox in community settings such as prisons, shelters, and schools. As a result, our primary goal has been to deploy our testing at vulnerable locations. Once we get a positive result, on-site staff are alerted and they can be more vigilant with clinical testing and disinfection of their facilities.

Living in Las Vegas, I can envision a future where every hotel monitors its sewage daily for viral levels. Such intelligence will help stakeholders decide whether their safety and ventilation interventions are making a difference. In addition, I believe that more tourists will want to visit Las Vegas, knowing that we go above and beyond to protect our residents and visitors.