From crumbling buildings and environmental wonders to the final resting places of Nevada pioneers and other waymarkers of the past, the Silver State is home to some of the country’s most unique hallmarks of history.

Preserve Nevada, a statewide historic preservation organization, is on a quest to save them with its annual list of the Silver State’s most endangered historic places.

“For two decades, we have chosen places that might be in imminent danger, or that might simply be in trouble if our community citizens or leaders don’t take action,” said Michael Green, chair of UNLV’s history department and Preserve Nevada’s executive director.

“As quickly as life in Nevada can change, we know that what is here today really might be gone tomorrow,” Green continued. “Our concern is that if we lose these priceless historical treasures, we can't get them back. And our hope is to expand the public's interest in maintaining important parts of our past.”

It’s an important venture, Green said, because history is often inextricably linked to current-day phenomena and beyond.

“If we lose sight of the past, we don’t know where we are in the present,” he said. “And it’s also a reminder that there’s a future in the past, if you think of the concept of preserving and protecting the buildings that are still out there, but also finding other ways to repurpose them to serve us and for us to serve them.”

For example, he noted that Las Vegas is well-known for its tourism-based economy that’s based on current and future trends. But there’s long been interest in vintage offerings throughout the state, such as the Mark Twain-themed Virginia City sites and museums dedicated to hospitality signage, mob, and atomic testing history. Green sees the potential for tapping into an expanded “heritage tourism” market. And Preserve Nevada is also working to partner with K-12 schools to infuse social studies curriculums with local historical information.

This year’s endangered places list highlights new items — such as buildings and cultural or environmental elements that acknowledge historical contributions by Nevada’s Italian, Basque, and Japanese residents — as well as repeat contenders from previous years where preservation efforts have stalled or failed to gain traction at all.

“Nevada’s history is a very diverse, sometimes inspiring, often very sad and difficult history,” said Green. “And whether it’s the tough stuff or the happy stuff, we need to preserve it and we need to be able to talk about it.”

Frontier Cemeteries

In the 1850s, hundreds of short-lived mining towns began popping up across Nevada. The harsh living conditions in these isolated towns made cemeteries an integral part of the communities. And when boom turned to bust, the cemeteries were the only traces of the past that remained. Later, fraternal groups and family members installed headstones for their loved ones. Occasionally, families visit to remember their ancestors with flowers. These flowers and cemeteries are an important record of the town’s existence.

The Nevada Legislature completed a cemetery survey in 1962 showing 3,000 of them around the state. The headstones and other grave markers have faced vandalism and sometimes removal. It’s important for the public to help keep these stories alive and preserve Nevada’s history for future generations. These cemeteries need public and private protection and stewardship.

Nevada’s Historical Markers

The legislature approved the creation of historical markers throughout the state in 1967. But after major state budget cuts in 2009, the program came to a halt — and maintenance of the approximately 270 markers has since suffered. The Nevada Division of State Parks is responsible for marker upkeep, but funding for repairs, replacement, updates, or expansion has not been included in budgets from the executive or legislative branches of Nevada government. As a result, several of the historical markers remain damaged or out of date.

Elko County Public Defender's office, 569 Court Street in Elko

Built in 1896 as the first publicly funded high school in Nevada, it has changed hands many times — serving as a library, the Elko County Manager's office, and now the Elko County Public Defender's office. It was originally a two-story brick building, but a fire during World War II led to it being re-roofed to one story. A small building on the back of the lot was built in 1905 or 1906 as the science building. There is talk of razing the building and replacing it with a parking lot.

Arborglyphs

These Basque tree carvings can be found throughout much of Nevada’s northern tier, where migrants from the Pyrenees brought their culture with them as they worked as sheepherders, ranchers, and restaurant and hotel owners and employees. Joxe Mallea-Olaexte’s "Speaking Through the Aspens" tells the stories of these carvings, what they say about Basques, and what Basques were saying through their art and words. Aspens typically live about 100 years, and efforts are underway to document the tree carvings. The Arborglyph Collective — Boise State University, California State University, Bakersfield, and the University of Nevada, Reno — received a grant in 2023 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to continue its work cataloging the carvings in hopes of creating a database.

Nevada Northern Railway Depot and Freight Building, East Ely, White Pine County

These buildings, which date to 1907, are two of the most important structures in the Nevada Northern Railway National Historic Landmark — one of the best-preserved railroad complexes remaining in the United States. In the 1990s, after the railroad ceased operations, ownership of the depot and freight buildings was transferred to the State of Nevada, while the rest of the complex became the property of the Nevada Northern Foundation. Today, the foundation is suing the state for unrestricted access free from the responsibility to maintain, repair or support. As a result, the proposed rehabilitation of the freight building, which was funded and slated to begin construction, has been indefinitely postponed. Moreover, emergency stabilization on the depot is underway, but desperately needed overall seismic upgrades have been put on hold until the legal issues are resolved.

Nishikida Laundry Building, 1403 US Hwy 395 N, Gardnerville

This is a rare property associated with Nevada’s Japanese-American heritage. The building opened in 1876 as the East Fork School, located 3 miles outside of town. It was closed in 1915 and moved to its present site in 1916. George Oka converted it to a laundry in 1918. The Nishikida family purchased the property in 1940 and operated the laundry until 1989. The building has since been unoccupied and was recently struck by an automobile. The city and owner are seeking Brownfields funds for cleanup and demolition. As Nevada was not included in the area subject to Japanese relocation during World War II, the Nishikida family remained in Gardnerville, with several members serving in the armed forces. One California resident of the family was released from a relocation camp to come live and work at the laundry during the war.

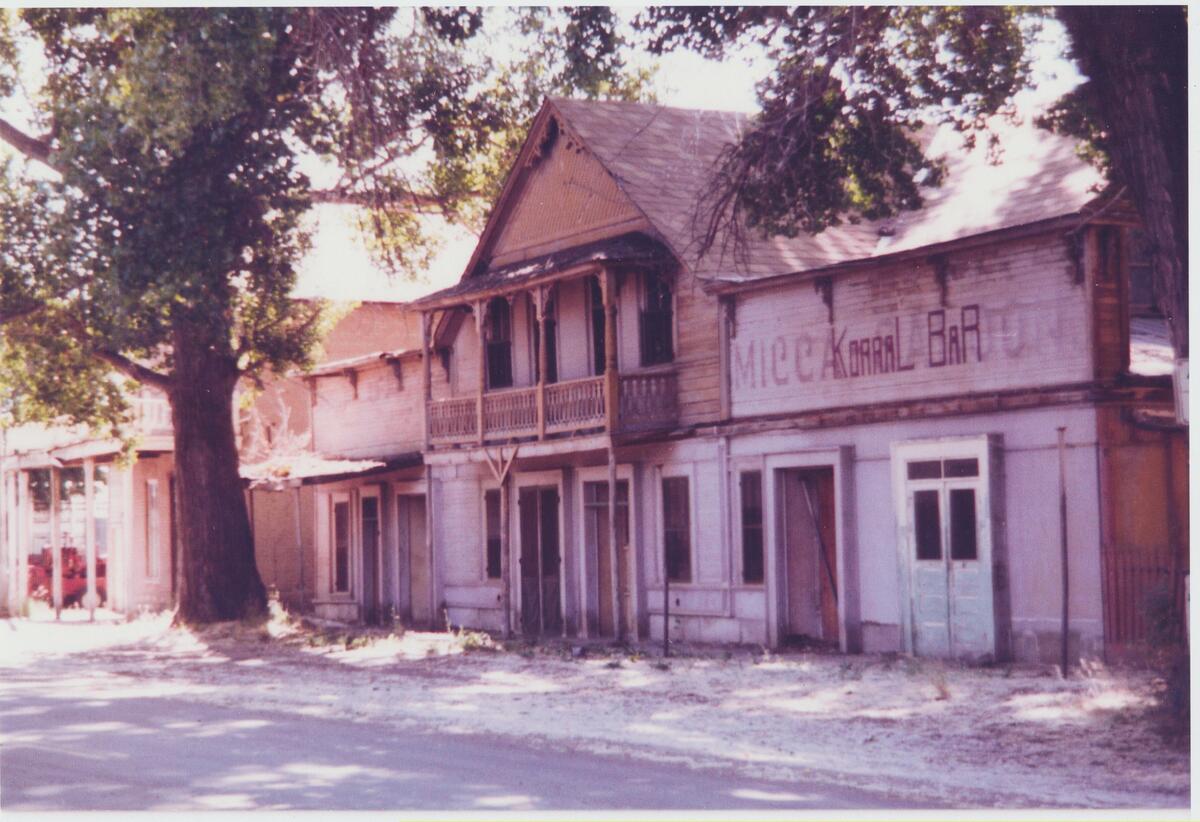

Micca House, 120 Bridge Street, Paradise Valley

Known as a favorite meeting place for the local Italian-American community, the Micca House is one of the rare Nevada examples of the Stick-Eastlake style of architecture left from the late-19th century Victorian Era.

The first portion of the building, erected in 1871 on Cottonwood Creek, was made of adobe and served as a warehouse for a dry goods and butcher shop located across the street. In 1879, a two-story adobe building was constructed directly to the right of the warehouse — housing a shoemaker, sundries store, pharmacy, and boarding rooms on the top floor.

Italian immigrant Alfonso Pasquale later purchased the property and, in 1905, enlarged and mended the two existing structures to create the Micca House, named for his village in Italy. Aiding Pasquale with construction were skilled Italian stone masons, who used granite from the nearby LeMance and Hansen Creek areas. The Micca House included a brick oven for baking bread; meat market with a cooler to house the meats; kitchen and dining room; offices of the Justice of the Peace; beauty shop; apartments; saloon; and storage rooms for food, coal, and ice.

Hannah’s Cabin aka Hannah’s Hideaway, Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park and Spooner Backcountry, Washoe County

Hannah’s Cabin is a modest log dwelling located in the Sierra Nevada high above the eastern side of Lake Tahoe. It was built in 1929 as a summer retreat for Hannah Hobart, the granddaughter of lumber baron William S. Hobart, Sr. The cabin is now part of the back country holdings of Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park. In 2015, the Nevada State Parks system said the property was in a state of arrested decay and needed stabilization and maintenance work within two to three years.

Old Mormon Fort

Nevada’s oldest existing structure, built by Latter-day Saints missionaries in 1855, stands in downtown Las Vegas as part of the Old Mormon Fort State Park. The park’s history includes serving as home of the area’s first post office, pioneer ranching families (including “First Lady of Las Vegas” Helen Stewart), the local Indigenous population, and chemical testing for Hoover Dam construction. But across the street, the City of Las Vegas has taken over the Grant Sawyer State Office Building and plans to raze it for a parking lot. The fort may well be secure, but destruction nearby and an uncertain future for the city-owned property and sports field next to the historic site is cause for concern.

Southern Pacific Railroad Resources of Reno and Sparks

The transcontinental railroad played a critical role in the founding and development of both Reno (1868) and Sparks (1904). And several historic Southern Pacific buildings are currently endangered due to long-standing vacancy, neglect, and encroaching development.

Of foremost concern is the 120-year-old Machine Shop building in Sparks. This massive brick structure is the last significant remnant of the huge Southern Pacific yard and shop complex that sparked the city’s birth and inspired its “Rail City” nickname. The Union Pacific Railroad has plans to demolish the historic building to clear the way for truck parking. In Reno, the former Southern Pacific Freight Depot (1931) — adjacent to Greater Nevada Field — sits underused and vulnerable, while the city-owned Southern Pacific Railroad Depot — built in 1926 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2012 — remains half-vacant and unimproved. In between, the American Railway Express Agency building (1926) is dwarfed by a newly-constructed parking garage just to its south.

Bethel AME Church, 220 Bell Street, Reno, Washoe County

Built in 1910, this modest brick church served as a center of worship, activism, and social life for Reno’s close-knit African American community for much of the 20th century. The congregation aided Black divorce seekers confronting Reno’s de facto segregation and the church served as a meeting place for Civil Rights organizations in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, the area around the church is the focus of intense private development. A recent attempt by developers to have the city abandon public streets and alleys in the vicinity would have severely affected access and viability for the church building, which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.

Historic Theaters

The Huntridge in Las Vegas and the Lear in Reno, both of which have long been endangered in various ways, are repeat contenders on the list because of their rich history. But there are countless others. A Southern Nevada group is working on preservation of the Gem in Pioche, and the Fallon Theatre is the subject of similar efforts. And then there’s the Crystal Theatre in Elko, the Nevada Theatre in Wells, the McGill Theatre in McGill, the Central and Capital Theatres in Ely, the Cinadome in Hawthorne, the Boulder Theatre in Boulder City — the buildings are still standing, but we must ensure that the physical structures both survive and thrive.