When a university launches a new area of study—particularly in a field as critical as health sciences—the goal is to recruit faculty with A-list credentials. So when UNLV’s recently renamed School of Integrated Health Sciences decided to establish a new Department of Brain Health, the college’s dean, Ronald T. Brown, went searching for a superstar.

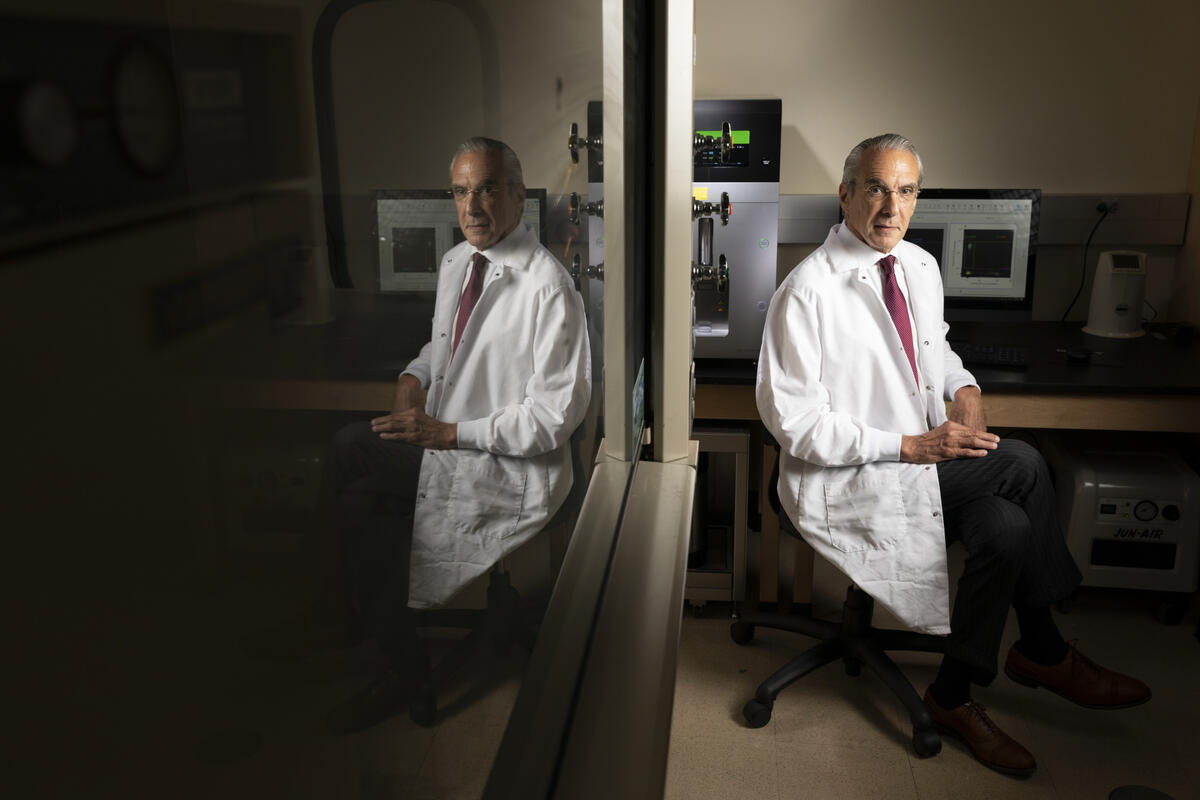

That search took Brown less than 10 miles up the road from campus to the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, where world-renowned neurologist Dr. Jeffrey Cummings had served as director for the center’s first eight years. Brown certainly knew of Cummings’ credentials, especially as it pertained to Alzheimer’s disease research—“Nobody could help but be interested in Jeff Cummings; he’s an icon.”

Health Care at Every Corner of Campus

UNLV's commitment to studying and improving health care goes beyond the School of Medicine. Disciplines all over campus are involved in improving the industry, from every angle.

While hosting some friends at his home, Brown had literature about Cummings spread across his coffee table. One friend who happened to be a neurologist spotted the material and asked Brown why he was researching Cummings. “I said, ‘Well, we’re thinking about recruiting him to come to UNLV,’” Brown recalls. “And my friend said, ‘My God—he’s it. He’s the man!’ I didn’t realize that then, because we’re always recruiting [faculty], and I hadn’t read through all his stuff.

“Then I got a little nervous: ‘Wait a minute—I hope we can do right by this guy.’”

Indeed they did, as earlier this year, Cummings agreed to join UNLV as a research professor within the new Department of Brain Health, which is chaired by Jefferson Kinney, an associate professor of psychology. In his new role, Cummings will focus on his specialty of Alzheimer’s disease research, including creating a new institution tentatively titled the Center for Transformative Neuroscience. He will also conduct community outreach to raise awareness and support for the new department.

For Cummings, it’s a welcome return to the world of academia, as prior to joining Cleveland Clinic he spent a quarter century at UCLA, where he served as director of both the Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and the Deane F. Johnson Center for Neurotherapeutics.

“I loved my time at Cleveland Clinic, but I also love the university environment and I wanted to return to a place where there was an emphasis on learning and discovery,” says the 71-year-old Cummings, who has earned numerous honors throughout his career, including the 2008 national Alzheimer’s Association’s Ronald and Nancy Reagan Research Award. “Also, as a new department, you have the opportunity to be far more formative than you do in a larger, more established department. So it seemed like the right combination of opportunities.”

Allied Health Sciences Marks Change to Integrated Health Sciences

For nearly 50 years, UNLV students who wanted to pursue a health sciences degree did so though the School of Allied Health Sciences, which was created in 1971. However, that’s no longer an option, because the university has officially bid adieu to the School of Allied Health Sciences. No, the programs and courses in the health sciences field didn’t disappear, just the name: As of late June, the School of Allied Health Sciences is now the School of Integrated Health Sciences.To the uninitiated, switching out the name “allied” for “integrated” may not seem all that significant, but in fact it was necessary to better reflect the broad range of health issues that are now represented in the school’s curriculum. “Allied health and allied-health professional just aren’t terms that are used anymore,” says Ronald T. Brown, dean of UNLV’s School of Integrated Health Sciences.

“Allied health sort of signifies an association with just physicians, but obviously in today’s world of health sciences, many individuals collaborate to provide peoples’ health care. So I thought the college should have a name that reflected the idea that we’re integrated and providing collaborative services for patients.”

Aside from the name, nothing about the School of Integrated Health Sciences has changed. It’s still home to the departments of Health Physics and Diagnostic Sciences, Kinesiology and Nutrition Sciences, and Physical Therapy. Also, the recently launched Department of Brain Health falls under the Integrated Health Sciences umbrella.

In all, the school offers nearly 20 undergraduate and graduate degree programs, plus two minors, a certificate program and a post-baccalaureate internship. Most importantly, students who earn degrees from the School of Integrated Health Sciences will continue to have little to no trouble securing employment in an underserved health-care industry. — Matt Jacob

With Southern Nevada’s aging population increasing rapidly, the need for exhaustive research into the cause of neurogenerative diseases—as well as the development of drug therapies—is greater than ever. As Cummings notes, 48,000 Nevadans suffer from Alzheimer’s disease alone. And while there are 112 drugs currently in the Alzheimer’s disease “treatment pipeline”—that is, drugs that are in various phases of clinical trials across the United States — the last new federally approved Alzheimer’s drug was back in 2003.

So because the number of people suffering from brain diseases continues to rise, and because the next wonder drug has been slow to materialize, Cummings says UNLV’s decision to create a Department of Brain Health was, well, a no-brainer. Throw in a partnership with the Ruvo Center—where Cummings continues to hold several National Institutes of Health grants and both he and Kinney continue to do research — and Cummings believes the department can quickly establish itself as a leader in neurodegenerative research.

“My research areas are going to be more focused on the strategies for optimizing new drug development,” he says. “How do we not just do clinical trials, but how do we do trials smarter? How can we look across trials and understand what went wrong and what went right? And how can we make trials better and better all the time?

“Besides [my work], there’s Dr. Kinney’s laboratory on molecular and biological neuroscience; there’s a translational biomarker unit where we measure biomarkers; and there’s an occupational therapy component. But the entire department is aimed at neurodegeneration and translational neuroscience as an approach to neurodegeneration.”

Unfortunately, a cure for such neurological diseases as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and multiple sclerosis remains elusive, but Cummings says there is some good news on the brain-health front. Thanks to resources like the Cleveland Clinic’s popular website HealthyBrains.org, the general public has become aware that improved physical health—i.e., better diet, regular exercise, reducing cardiovascular risk factors, etc.—is tied to improved brain health. In other words, significant strides have been made on the prevention side.

Of course, there are no guarantees, particularly for those who carry certain gene traits that make them susceptible to contracting neurological maladies. And so scientists, research facilities and academic institutions continue their fight for a cure. And Cummings, for one, wouldn’t be surprised if UNLV’s new Department of Brain Health eventually is at the forefront of a critical breakthrough.

“What you need is resources to attract the right people—if you get the right people in place, anything can happen,” he says. “Yes, we’re only at the beginning and there are just a few of us. But can [a breakthrough] happen here? Absolutely it can. And if you look back at the origins of almost any [successful] program, they had a small beginning and they grew into something large because they had passion for it, people got interested in it, and resources were provided for it.”

And having someone as respected as Cummings on board can only help generate those resources and boost the department’s profile. “It certainly helps recruit faculty, because everybody who works in the area of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease knows of him,” Brown says. “And as universities do good work, people begin to invest in them. The federal government begins to invest by means of grant dollars, and donors invest through philanthropy.”