Dave and Mindy Rice's son, Dylan, is an enthusiastic 10-year-old with a lot of hobbies under his belt, a smile for everyone, and a fascination with re-enacting Broadway musicals.

"He loves life. If everyone in the world were as happy as Dylan is every single day, the world would be a lot better place," said Dave Rice, head coach for UNLV's Runnin' Rebels. "He's someone who actually enjoys affection. He likes to give people hugs."

"Sometimes whether they want it or not," Mindy Rice laughs.

But Dylan's personality didn't bloom as quickly as other children's. As a toddler, Dylan had reached some of his milestones early, but was struggling to communicate. His older brother, Travis, hadn't experienced the same difficulties that Dylan was having.

"We were first told it was speech delay. We started with that route," Mindy said. "But as he got older, you could tell there were other things he wasn't catching on as quickly as he should have."

Finally, after three years of subjecting Dylan to tests and doctor visits and after a nine-month wait to see a specialist, Dave and Mindy Rice thought they'd get an answer.

A renowned doctor based in Utah, where the Rices were living when Dave coached for Brigham Young University, diagnosed then 6-year-old Dylan with autism. But, he stopped short of providing guidance on how to make things better for him. The Rices were left with a statement that still haunts them.

"He told us to start a trust fund for Dylan," Mindy said.

That was it. Their reaction? "Devastated. Frustrated," Mindy said, trying to hold back the tears.

Dave's reaction, Mindy said, was of a coach who knows his team can beat the odds. He wasn't going to let someone tell him "this was the way it was going to be." So the Rices created a new game plan.

They tapped into their network of friends to find others whose kids were also diagnosed with autism. Friends talked about the characteristics their kids shared -- walking on toes and pointing to things but not speaking. They eventually found resources to help Dylan and feel fortunate that they had the means to get their son extra help. Now they want to help families facing similar challenges.

A Platform

The Rices, both UNLV graduates, have considered UNLV and Las Vegas home for more than 20 years. Dave played on the Runnin' Rebels NCAA championship team in 1990 and then went on become an assistant coach. He returned to UNLV in 2011 as head coach, a position that affords him a unique platform for influencing the community off the court, he said.

"I think fathers particularly have trouble coming to grips when their son or daughter is diagnosed with autism and it doesn't have to be that way," Dave said. "And for me to stand up and say 'Hey, it's OK.' I think it's a positive message."

In personal conversations and public settings, Dave Rice talks candidly about his son, and the challenges his family faces. Families shouldn't feel like the diagnosis brands them with a letter "A" for autism, as if it's a life sentence, he said.

"There's such a stigma that's associated, and it doesn't need to be that way. Look at improvements that our son has made," Dave said. "He's mainstream in school. He's happy. The quicker we were able to get intervention, we knew the better off he would be."

In early 2012, the couple established the Dave Rice Foundation to fund autism programs, resources, and education programs in the Las Vegas Valley. Its goal is to help fill in gaps of existing groups.

"We want to be on everyone's team," Dave said. "There are a lot of organizations in town that do a lot for autism. We're not the only ones doing it. This is not just (mine and Mindy's) cause; this is 'our cause' as in everyone's cause."

Last July, the Dave Rice Foundation donated $100,000 to the UNLV Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders, allowing it to add comprehensive testing for children and adults to its community services. The donation will also expand the workshops that the center already offers to parents, healthcare providers, and professionals such as teachers.

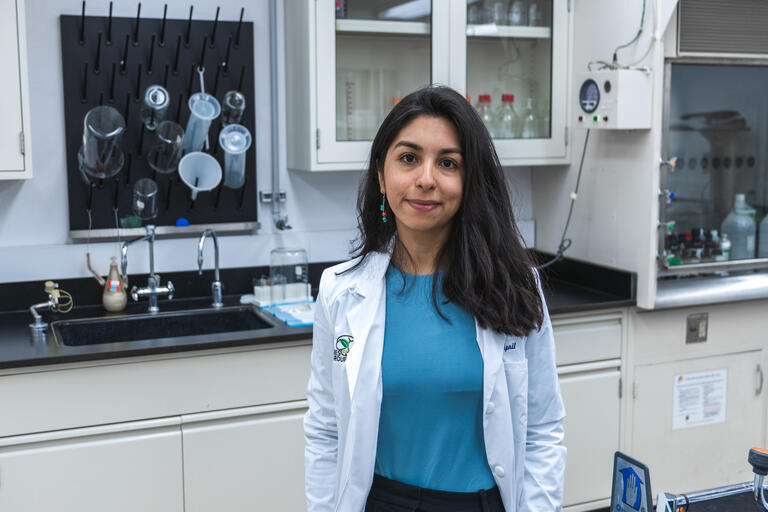

Qualified resources for autism testing in the state are limited, said Shannon Crozier, director of the center. Autism testing can be expensive and therapies to help kids who receive the diagnoses can also add up. The center provides its services based on income at a sliding scale, Crozier said.

UNLV faculty and graduate students will administer the psychological, speech, communication, reading, and behavioral skills tests needed to diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-related developmental disabilities. Symptoms vary from person to person and can begin before the age of 3. Generally, children with ASD have trouble with language and social skills, and show unusual behavior with repetitive patterns that can result in tantrums, obsessions, aggressiveness, and self-injuries.

"The longer children go without treatment, the worse their condition. By identifying ASDs early on, the likelihood of improved behavior, communication skills, academic, and behavior skills increases," Crozier said. "Parents can better understand ASDs and what strategies can be put in place to help their child."

The Rices wonder where Dylan's development would be today had they received the correct diagnosis sooner. Sometimes Mindy wishes she could go back to the doctor who had little hope of Dylan having a normal life and say, "Look at him now."

No parent should have to feel like there's no hope or help available, she said.

Members of the public may visit the UNLV Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders or call (702) 895-5836.