While millions of children begrudgingly lug hefty backpacks filled with school supplies, snacks, and other belongings, one group of UNLV researchers is asking whether those same bulky sacks could someday serve a higher purpose: aiding in the therapy of children with autism.

Through the UNLV Graduate College’s Rebel Research and Mentorship Program (RAMP), Janet Dufek, associate dean and professor in the School of Allied Health Sciences; Jeff Eggleston, a doctoral student in the Kinesiology and Nutrition Sciences department; and Mieko Mamauag, an undergraduate student in the same department, have teamed up to find out.

Their research project, “Examining the Influence of Backpack Weight on Trunk and Stride Kinematics Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder,” explores whether children with autism experience movement challenges when walking with a backpack on. But the word “challenges” may be a bit of a misnomer. Such challenges may prove harmful, but they may also prove helpful, should they make children with autism more efficient walkers.

“In the scientific community, there are two schools of thought with this clinical population: One is that if you give them a more difficult task, they will focus on it and improve performance,” Dufek said. “The other is that it is so foreign to them that they’re all over the place with their movements. But if we can direct the focus of a child with autism, that could be a great thing.”

According to 2014 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in 68 American children has autism. In 2004, just 10 years earlier, the prevalence was 1 in 125. This growth, the Autism Speaks organization indicates, makes it one of the fastest-growing developmental disorders in the United States.

The RAMP team’s research not only raises awareness about a disorder but also tackles it from a biomechanics angle that to date has rarely been studied. According to the researchers, children with autism may experience trips or stumbles more frequently when faced with walking obstacles like stairs, curbs, and unfamiliar surfaces. Through their research, the group hopes to determine if the added weight of a backpack can help these children walk more safely and efficiently.

Employing weighted objects in therapeutic treatment plans for children with autism is nothing new. Weighted vests, blankets, and more have been utilized by children with autism, under the assumption that the added mass benefits them from a behavioral perspective, encouraging calmness and focus. How weighted wearables might affect their motor skills, however, is largely uncharted territory.

“In the biomechanics world, there’s no other group that is examining these data the way we are,” Eggleston said. “If we can use a backpack to mitigate potential walking hazards—the tripping, the stumbling—and in turn [the children’s] behavior improves too, we address two issues with one intervention.”

Additional perks of the object they’ve placed their hopes in: Most children already use backpacks (versus weighted vests, which could draw attention to a wearer), and anything already lying around the house can be placed inside a backpack to weigh it down, saving families money.

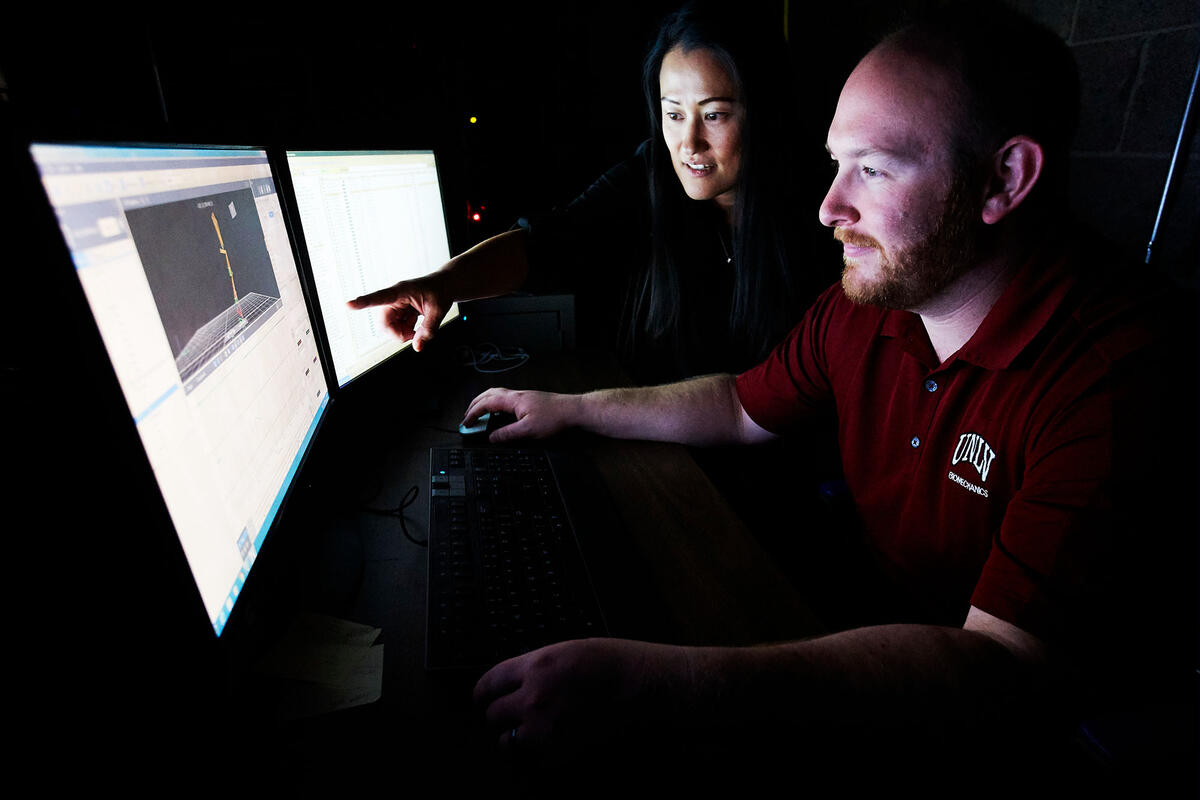

A total of 11 children with autism between the ages of 5 and 17 participated in the project’s initial data collection phase, which spanned four months. The researchers began by weighing the children. Next, the researchers placed reflective markers on the children’s trunks and lower extremities. Then, the children walked—first without weight in the backpack they were wearing, then while carrying 7.5 percent of their body weight in the backpack, and finally carrying 15 percent of their body weight in the backpack. Ten infrared cameras placed around the laboratory captured the children’s steps and produced three-dimensional representations of their movement patterns that the researchers will later analyze using computer software.

Whereas current autism therapy approaches are based primarily upon psychologists’ observations, the RAMP team’s work has the potential to serve as a quantitative diagnostic tool—one that could enable early intervention.

Mamauag, who hopes to open a physical rehabilitation center of her own one day, is particularly excited about the project’s promise. “Hopefully, in the future, I can utilize what I learn from this research project in my practice and better treat patients,” she said.

Eggleston and Mamauag presented the RAMP team’s findings at the Northwest Biomechanics Symposium in May at the University of Oregon.

RAMPing Up Research

Launched in the spring of 2016, RAMP teams a faculty member, graduate student, and undergraduate student together on a research, scholarly, or creative project. RAMP’s 2016-17 cohort includes six pairings of graduate and undergraduate students with a faculty member.

Along with the benefits gained from working side-by-side with their faculty mentors, graduate students gain mentorship skills, as they are also responsible for serving as mentors to their undergraduate counterparts, and undergraduates gain new research skills and an additional adviser by participating in the program.

Dufek, Eggleston, and Mamauag have found their research together rewarding in a number of ways.

“I’m very passionate about research and getting students involved in it,” Dufek said. “Certainly the most rewarding part for me is seeing the research growth—seeing that light bulb come on for the undergraduates and observing the maturation of a doctoral student’s research.”

Eggleston noted the direct impact the RAMP team’s research has already had on the parents of the children who participated in the project. “We hear a lot of, ‘We’ve been on waiting lists and waiting lists, and we appreciate that you’re doing research and trying to learn more,’” he said. “For me, it’s rewarding [to know] the parents of these kids are so grateful that we’re actually doing something.”

Mamauag pointed to the practical application of what the RAMP project has provided her. “Learning the research process from the beginning has been very rewarding,” she said. “What I learn in class, I’m actually using in research.”